Some time back

started a section of his Racket News stack called The Writing Life, where he shared tips and memories about how he became the urbane man-of-letters he now is (love that guy). One of those articles discussed the first work of fiction that had an impact on him, when he was 14. I was struck by the idea, and since imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, I decided to flatter Taibbi and have a think about my own “first work of fiction that had an impact on me”. Spoiler alert: for better or for worse, it’s Conan.I was in 5th grade in 1983, give or take. I was 9 or 10 years old, my August birthday coupling with the fact that I skipped kindergarten (it’s at the top of this substack, yo) to render me one of the youngest kids in class. The time had come for the school book fair. As far as I know, these events still happen, and you probably remember them from your own time in elementary school. Back in the day, some flavor of local bookstore, almost certainly operating in cooperation with one or several publishers, would take over an elementary school cafeteria (later the library) and turn it into a pop-up book shop for kids for a day. I, like the other kids at Grant Elementary in Riverside, California, begged my parents sufficiently for five or ten dollars to go get cheap paperbacks.

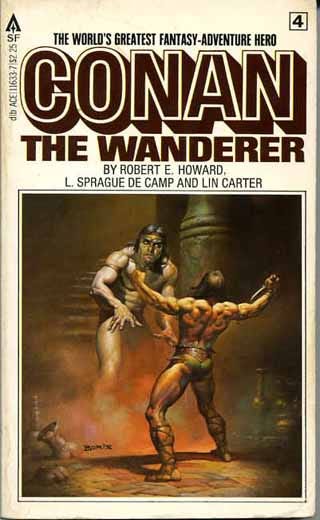

I came home with, so far as I can recall, two paperbacks and a poster. One of those paperbacks was the original Thieves’ World anthology, edited by Robert Aspirin. It was certainly a book I enjoyed, for reasons not part of this bit right now. And the poster (“The Invisible Thief,” by Steve Hickman) is still hanging on my wall (a poster I bought for probably 50 cents in the 80s now sitting in $100 worth of custom frame from Hobby Lobby, because priorities). But neither of those are what I’m writing about today. I’m writing about the other paperback I took home that fateful day, which was this:

This too, was an anthology, this time of stories featuring Conan the Barbarian. One of those stories, “Shadows in Zamboula,” became the touchstone for pretty much my whole reading life to follow.

Originally published in the November 1935 issue of Weird Tales magazine, this story has everything: Conan, a cannibal death cult, a naked slave girl, an evil priest-wizard, a hulking henchman (who Conan must strangle to death), magical smoke-snakes, a temple to a horrid ape-god, a scheming innkeeper, a doublecross, a curse that must be lifted, treasure, peril, violence, violence, peril, a for-real twist ending, and did I mention the naked slave girl?

This story blew my 10-year-old mind.

That this book was lying in wait for me at the elementary school book fair should probably be shocking. Who thought this was a good idea? I suppose we can blame whichever indie bookshop spearheaded this particular book fair, but “blame” may be too harsh a word. In 1983, fantasy fiction was picking up steam, and anything with swords and sorcery involved was landing on book fair tables all over. That included old pulp revival anthologies: Howard’s Conan, Lovecraft’s Mythos, and other such stuff (if I say “Appendix N” and you know what I mean, you might be one of my people).

But anyway, regardless of the reason, this book ended up in my backpack and this story ended up in my head. It remains the gold standard against which I judge all fantasy fiction that crosses my path, the undisputed champion story in my personal fantasy catalog.

Why?

“Shadows in Zamboula” packs all of its everything into a concise space. There’s no padding here. In the original publication, “Shadows in Zamboula” was 20 two-column magazine-size pages long (public domain being awesome, the version I’ve posted for posterity here runs to 30). In those pages was a whole story which was happening in a whole world. The story had weight. It existed in a world that had history and heft. The characters populating the story had names, labels, and descriptions that were enough to give me something to build a mental picture, but not enough to descend into silly stereotyping. These were people, places, and action from a beforetime; modern sensibilities had no bearing on this narrative. It was transporting, a glimpse into a savage (nakedly savage, heh) world where civilization was tissue thin and everybody knew to lock their doors at night.

Into this world rolls Conan. He’s broke, having caroused away whatever loot he escaped the last story with, but with just enough coin left to cover a cheap inn room before he has to blow town in search of new opportunities. That inn stay turns into an encounter with representatives from the local cannibal death-cult. This goes poorly for the representatives of the local cannibal death-cult, but certainly accelerates Conan’s timetable for leaving town. Only he can’t leave just yet, because on his way out he rescues a naked slave girl who for her own reasons finds herself regrettably out of doors at night in Zamboula, where she almost becomes a meal for a second pack of cannibal death cultists. She’s grateful for Conan’s rescue, but not THAT grateful (if you know what I mean, and Conan sure does). Still, she holds out the idea of being THAT grateful if only he will help her with this problem she’s having with the local evil priest-wizard. Men have killed for less, and Conan is a man, so off they go to the temple of Hanuman the ape-god and a fateful showdown with Totrasmek the high priest.

I defy you to not want to know what happens next, even just a little bit.

Even now, a story needs to get moving or I’m probably not going to stick around. I never found out how The Wheel of Time ended. Surprised? You shouldn’t be. I couldn’t read Lord of the Rings until I was in college. Not didn’t. Couldn’t. It just moved too slow for me. A great story, sure. One of the touchstones of the entire corpus of fantasy fiction. But I started Fellowship a half dozen times before I could care enough to plow through the rest.

I suspect this is part of why I dig Substack. The writing here is shorter-form. Get in, make your point, and get out. If you have more to say someday, say it then. For now, speak your piece and be done. I can respect that.

This broad respect for the concise is supported by four big things I learned from Conan in “Shadows in Zamboula”. You can read the story once as a slam-bang action piece, and then again to parse through Conan’s actions and decisions. For a kid growing up and looking for life-rules, this was a rich vein for me to mine. It still is. Let’s talk about what this story encouraged me to be.

Be alert

The action kicks off for Conan when he is awakened by a scraping at his inn-room door. The story points out that Conan, honed by his hard barbarian life, awakens instantly, ready for fight-or-flight action. I am no Cimmerian honed by a life of danger and hardship, but being alert to danger never goes out of style. It is easy in today’s world to be inattentive and distracted. Understand this, and don’t let yourself stop being alert.

This concept includes readiness, too. Not only does Conan awaken ready for action, he’s kept his sword close, and doesn’t have to fumble around for it in the dark. This has lots of modern application, summed up in a simple statement: I carry a pocketknife.

Be flexible

Conan’s plan changes four or five times over the course of the story. He has no idealized world view blinding him to the real things going on around him. He fully understands that nobody owes him anything and nobody cares about his feelings. As such, he can shift as new plot points arise. We all live lives where new plot points arise. Seeing things as they are lets you adjust. Clinging to delusive ideological phantoms leads to paralysis. Avoid paralysis.

Be decisive

Speaking of paralysis, Conan grasps the situations he finds himself in quickly, and adjusts immediately. He has at least three opportunities to just get out of town over the course of the story, but actively chooses to help Zabibi the slave girl through to the end of her perilous errand. He’s got reasons, sure (if you know what I mean), but the fact remains that he makes his decisions and stands by them. He doesn’t second-guess. He decides, and goes.

Be smart

At several points in the story, Conan is revealed to know more than anyone expects about what’s going on. He never gives away that he knows more than he should until it matters. He does not brag or monologue about how smart he is, which leaves space for everyone around him to underestimate him. Having been underestimated, he moves decisively to win.

I can’t think of anything smarter than not bragging about how much you know. Knowing is an advantage (it’s half the battle, y’all). Not revealing you know until it matters exponentially increases that advantage. Conan is strong AND smart. The combination makes him awesome.

Live your life

Which brings me to the big wrap-up takeaway for my fifth-grade self, carrying forward even to today: your life is yours to live, and you should LIVE it. It doesn’t matter what other people read or what other people like or what other people think you should do. You get to like what you like. You should be open minded about the journey (Conan sure is), but ultimately you’re the boss of you. Decide what you want out of life, and then go get it.

Your life is yours to live, but that doesn’t mean you need to be selfish, just honest. Your life is also yours to give. You can give it to whichever cause moves you. Just be honest with yourself about what you’re doing and why. Conan sure is. I strive to be likewise.

I've used his self assessment to help a lot of people. Conan wakes up in a cell after getting mobbed. Alive, check, not bleeding out, check, no major broken bones...you get the picture. Doing this really helps folks who are overwhelmed. Once they get to what's bugging them, they have a big old list of what's ok. And I found Conan books right about the same time as you. Great influence on life.

I loved anthologies as a kid and still love them. Solid article.